Art Thoughts v.2: The Hammonds House Museum

Exhibition Review — Sacred Space: Brandywine Workshop and Archives

Since I began screen printing, my appreciation for various printing methods has taken center stage in my practice. Screen printing has given new life to old work. Virtual images are put on paper through a hands-on ritual. It’s a process that requires patience, presence, and flexibility. This physical act has taught me the many ways a picture can exist in print. From photography, drawing, or painting, it’s always impressive to see a work that existed in another medium live on in a new form. So naturally, I now notice artworks that are silkscreen (screen prints) or lithograph prints (watch this short to see the lithography process).

I recently learned about the Hammonds House Museum and discovered their group show featuring offset lithograph prints from the vaults of The Brandywine Workshop and Archive. These are two historical Black art institutions I didn’t know existed.

This Artletter is dedicated to The Hammonds House Museum, Brandywine’s Workshop and Archive (BWA), and their show Sacred Space. I briefly share both institutions’ histories, my thoughts on the show, and some of my favorite pieces. I hope this Artletter nudges you to look more into the Hammonds House, BWA, and these artists, for there is so much more to learn and be inspired by.

My experience at the Hammonds House Museum reaffirmed what I’ve always known: Black institutions, spaces, and museums m a t t e r. Having access to historically Black environments and institutions helps us learn, remember, and continue what those before us have started. We must support them.

And sometimes, that support is as simple as talking about them.

”Artists’ responsibility is to keep our (artists’) legacies alive.”

- Kerry James Marshall

With Love,

Ciarra K. Walters

Dr. Hammonds & the West End

The Hammonds House Museum was established in 1988, following the passing of the prominent Atlanta physician and avid art collector, Dr. Otis Thrash Hammonds. After his death, the Fulton County Board of Commissioners acquired Dr. Hammonds’ home and his collection of 250 artworks, transforming the space into a museum dedicated to visual artists of African descent.

Nestled in Atlanta’s historic West End (one of the city’s oldest Black neighborhoods) the Hammonds House Museum sits blocks away from the Atlanta University Center (AUC), home to Morehouse, Spelman, Clark Atlanta, and Morris Brown.

This home-turned-museum is truly iconic. Between its Victorian-style details, sculpture garden, abundant natural light, and a cozy yet elegant familiarity, it’s a museum like no other. Walking in, I felt like I was stepping into the home of a beloved, wealthy relative. From the glossy wooden floors to the patterns of its wallpaper, Hammonds House carries a timeless, welcoming essence, reminiscent of the feelings I had for the Underground Museum (RIP). Unlike many large museums that can feel overwhelming, this space is intimate and inviting, making it an ideal experience even for those who don’t typically visit museums. For those who do, it gives you a fresh take on art and the spaces it can exist in.

A museum’s history isn’t usually something I pay much attention to. More often than not, Black people weren’t allowed to attend, and Black artists weren’t being collected. This experience was significant because of the Hammonds House’s history. Knowing that this house once belonged to a Black man who collected and supported Black art before it was popular creates an energy that can’t be duplicated or felt in most museums.

Brandywine Workshop and Archives

The Brandywine Workshop and Archives (BWA) was born in the garage of artist and educator Allan L. Edmunds in Philadelphia in 1972. What began as a creative space for local youth has grown into a nationally recognized nonprofit cultural institution dedicated to printmaking, artist residencies, education, and community. BWA houses a digitized permanent collection of over 1,400 prints, offers exhibitions and internships, and continues to champion artists of color through its collaborative and inclusive approach to artmaking.

In 1975, Edmunds joined forces with abstract artist Sam Gilliam to launch a visiting artist residency that would go on to host over 450 artists (and counting), including Howardena Pindell, Deborah Willis, Betye and Alison Saar, Barbara Chase-Riboud, Romare Bearden (their first resident), Melvin Edwards, Jacob Lawrence, and many more.

Their history is rich and long, and for the sake of this Artletter, I must get to my art thoughts (lol). To learn more about BWA, read this and watch this short interview with Edmunds below.

Art Thoughts on Sacred Space

The exhibition Sacred Space: Brandywine Workshop and Archives features prints from BWA’s collection spanning the last five decades, exploring “the interconnected realms of spirituality, time, space, memory, and culture.” It was originally curated by Juanita Sunday for Fairfield University Art Museum (see show here), and while the Hammonds House Museum version shares the same prints, it was curated by Halima Taha.

Here are three things that stood out to me.

Artwork Selection: I loved the selection and curation of the prints. These prints added to the sacred space of the Hammonds House. I love the blend of abstract and figurative prints. Although each print is different, they all felt like they were related.

The Wall Labels: One thing that stood out to me was the artwork labels. While they included the usual details—artist’s name, title, date, medium—they also featured a photo of the artist and a quote in their own words. This made a huge difference. There were a few prints I overlooked, but after I read the artists’ quotes, I spent more time with their prints. Including an artist’s portrait and voice alongside their work creates a personal bond between the viewer, the artist, and the art.

Playlist: HHM created a 69-song playlist for the exhibition that played in the lower galleries. I am noticing more museums playing jazz in their exhibitions, and that’s the way I like it. It makes the space feel less intimidating and more relaxed.

My Favorite Prints

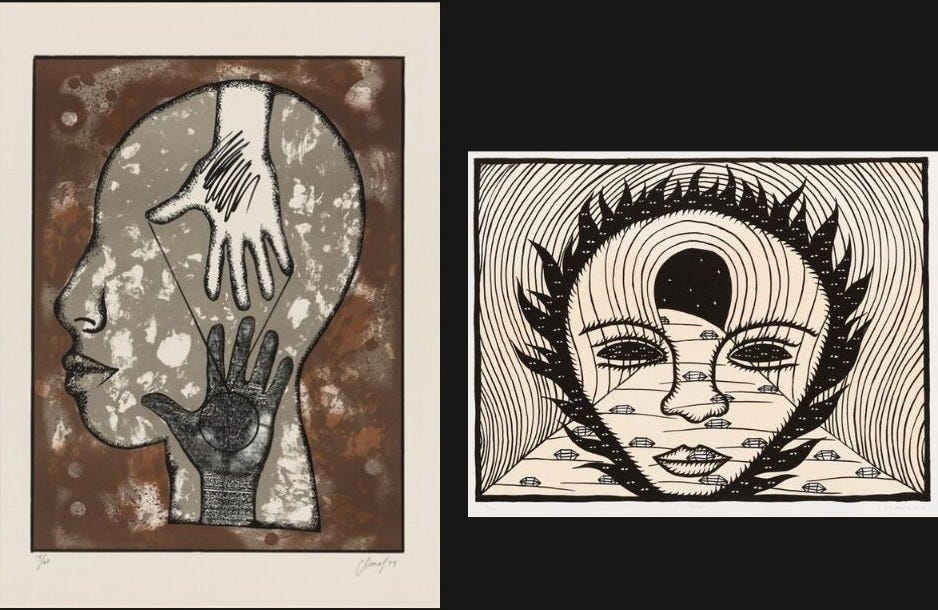

Untitled (Hands/Head), 1999 & El Tunnel, 1999

Untitled (Hands/Head) first made me question what the hands were reaching for and why one hand was white and the other black. To me, the black hand is the body, and the white hand is a spirit. The string between both hands shows the interconnectedness between the physical body and the spiritual realms. And our brain is the bridge between the two. I love everything about this print. From the tones, shading, and shapes, it is subtle, but it’s like a puzzle. There is something there to figure out.

El Tunnel instantly tripped me out. This floating head is made up of eyes and lines. There is hole in the middle of the forehead, a tunnel to the third eye. I love how the pathway to the third eye is covered in gemstones. I thought about all the “gems” we receive when we’re tapped in with our third eye. It feels otherworldly, connecting space to our human consciousness.

Until the Magic Comes, 1992

The piece brought up so many questions. Why did this little figure have a noose attached to its head? Why were its arms crossed? Does it look annoyed by the couple? Was it even looking at the couple? When I saw the title, Until the Magic Comes, I thought, what magic?!

What intentionally grabbed my attention was the bright colors. They are the same shades as a moody sunset, which I think is fitting for this moody and mysterious piece. The couple looks like they are making love, and their expressions look tender and sweet. They are turned horizontal, while the strange character stands vertically. It is off-putting, almost looking like two separate pictures. It is unsettling, but intriguing at the same time.

Untitled (Color), 2006 & Building Myself, 1996

Untitled (Color) is so stunning in person. The imagery and vibrant colors made me think about Mexico. In Alvarez’s quote, he says, "My main inspiration is the border. I want the audience to experience that particular reality through art…My works have been forged through the beauty and cultural richness of the border and also the very limitations of the region.” It made me think about the people who live along the borders of our country and others.

Building Myself is one of my top three favorite pieces from the show. I love that a man made this. It feels feminine, but also masculine. I interpreted it like this: This man is ‘building himself’ in nature. He’s out in nature looking up at the moon (eternal wisdom), and the spiral in his chest represents the eternal energy swirling inside him. As both the moon and spiral glow, I see their spiritual connection. His atmosphere blends into him, reminding me of our undeniable bond with nature.

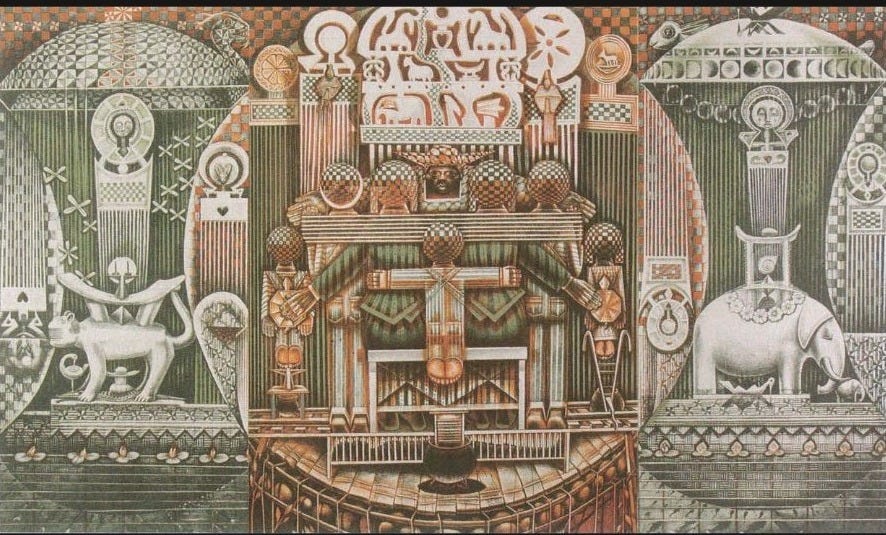

Family Arc, 1992

Family Arc is a triptych (three prints). This work reminds me of Diego Rivera’s murals, shrines in India, temples in Asia and Egypt, and African art. Although made in 1992, this print feels older, almost ancient. In this print, we see the many phases of the moon, animals, and a Black man with shades, a funky hat, and his arms stretched out. He reminds me of the figure in Charles White’s Black Pope (Sandwich Board Man).

Below him, a little boy kneels with his arms stretched out, creating a cross. Between the title, religious iconography, and this cool Black man...let your imagination run wild.

Portal, 1990 & Songs for Our Fathers, 1994

I love Portal for its African imagery and bright hues. The bottom middle sculpture looks like antennas magically controlling the sculpture on top. When I see this, I see motion. Like the title, this piece feels like a portal. Payton’s quote was “When I'm in the studio, l'm in conversation with everyone who ever made an image that I saw." I felt that.

Songs for Our Fathers had me a little choked up. I was drawn to this one because of the photographs, but after reading the title, I could feel this piece. I mainly see artwork highlighting mothers (as they deserve), but rarely do we see art about fathers. This felt like a beautiful homage to Black fathers. I thought about how jazz and blues musicians sang, said, and played the notes and words their fathers could not.

Quest: We Who Believe in Freedom Cannot Rest, 1993

I see slave ships so often in artwork, I’m numb to it. I look away quickly when I see them, but for some reason, I stopped at this one. I read the artist Bennet-Olomidun’s quote, “Art speaks for itself,” and laughed —straight to the point. Then I saw the title, Quest: We Who Believe in Freedom Cannot Rest, and it felt like it hit me in the stomach.

Seeing a photo of a happy Black couple over two slave ships evoked such strong emotions. During these unprecedented times, when giving up sounds easier, we have to remember: we who believe in freedom cannot rest.

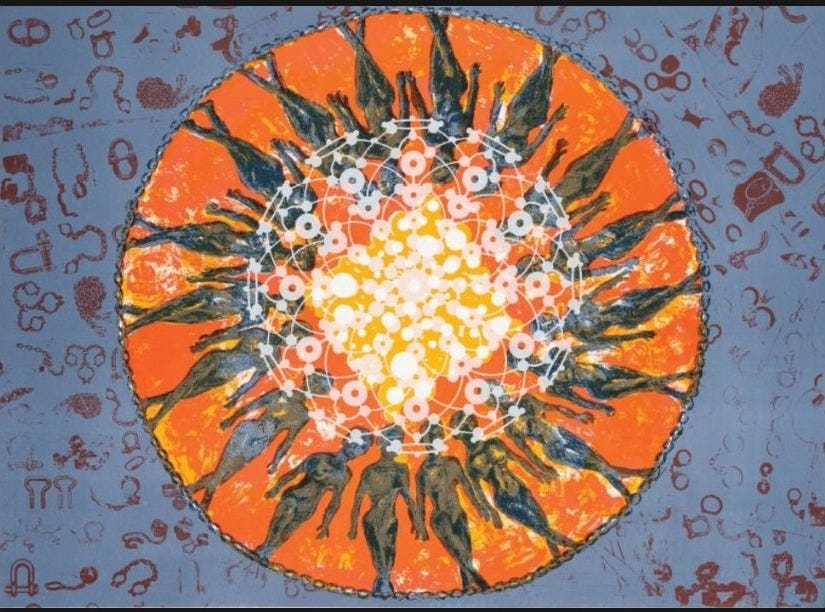

Veil, 2019

Veil feels like the cosmos, infinite energy spinning together. This work feels alive, like an organism under a microscope. As I looked closer, I realized the red objects were chains and cuffs. Suddenly, a piece I thought was light and airy became heavy. It made me wonder, what are these women doing? Were they ancestors? Were they women who were freed? Were they in a nebulous? Are they the nebulous? So many questions. Only time spent looking will answer.

Thank you for reading! Please share your art thoughts! xx Ciarra

Will have to visit the Brandywine Museum! Thanks for sharing